Source: Ken Schultz Tweet

This post is designed to be a non-comprehensive collection of useful information and tools to produce quality online education. As one of the most international Universities in the world, CEU is looking to duplicate a large proportion of their courses online for incoming students who may or may not be able to come to our brand new Vienna campus and take part in our traditional courses. CEU is quite different from most universities. We only do social sciences and humanities and we only have grad students. (Starting this Fall we will also have undergrads, but the vast majority of our training remains grad training.) Needless to say, most of us were also not prepared for the disruption in how we do things earlier this year. I personally would not have known anything about this either but while many of my colleagues were reverting their courses to emergency measures, worrying about what they need to do tomorrow so that their classes do not fall apart, I was not teaching. Still, my circumstances required me to figure out the online education thing fast. (At least I had the time to do it.)

I am putting together the most useful videos I found to help people visualize, conceptualize and deal with the task at hand. I am also sharing experiences in the text. Hope it will be helpful.

A Bit of Background

(Feel free to skip to the next section if you just wish to quickly get to the resources.)

Along with two colleagues, Derek Beach from Aarhus University and Benoît Rihoux from the Catholic University Louvain, we have been responsible for the academic content of the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) Summer and Winter Schools of Methods and Techniques, two events that run over 100 courses and service close to 1000 people every year for graduate level social science methods education. By March it has become blatantly clear that ECPR will not be able to run the Summer School, hosted by CEU since 2016, in its traditional in-person format. The three of us, with the help of one of our instructors, Cai Wilkinson from Deakin University in Melbourne – famous for its online Cloud Campus, spent what feels like a full time job rebuilding our Summer School offer, recruiting instructors who were either experienced with or excited about investing in high quality online graduate social science methods education. We have been playing with the idea of developing an online offer to complement our in-person event maybe for 2022/2023. (We even had a meeting planned for late spring in Florence, Italy to brainstorm it out. Needless to say, no in-person meeting took place in Italy but the timeline accelerated fast.) We quickly had to become experts in the pedagogical model and get creative in sorting through what would and what would not work for graduate social scientists. We personally ran two pilot workshops (one on Process Tracing and one on Multilevel Regression Modeling) to test out ideas, infrastructure and to gain hands on experience with the pedagogical model. Our instructors are looking to us for guidance and we are preparing the materials to support them. Our new event, on opening day registered people for ¾ of the slots available and landed 40+ people on the waitlist for their preferred course. Now we are working on expanding our offer to accommodate everyone else looking to participate. At the same time CEU made the decision to duplicate its offer between online and on-site for the Fall. For these two communities, I am hoping the following materials will be a useful curation of the hours and hours of videos I watched trying to sort out what is useful and what is not.

First, while the emergency teaching happened synchronously as all of our students were at either our Budapest or Vienna campuses, this model will not be the most appropriate for the Fall when most of our students will be scattered around the globe. We need a model that overcomes tech and connectivity issues people may have. The best way to do this is to rely heavily on asynchronous components of teaching, augmented by synchronous interactive components. It is important to ensure that students feel connected to both the instructors and to each other, to feel like they still are part of a learning community and receive a high quality educational product. Tools that best achieve this are tools we could and should have used in our regular classrooms for a while already, we just did not know about them. Many of these tools will be useful to enhance also our regular teaching.

(There is a lot of research around pedagogy. Here I will predominantly focus on the basics, the technology, the hands on how-to and the tips and tricks to improve production value of the course. CEU people, please check out the Center for Teaching and Learning materials to get a more comprehensive picture on pedagogy. They have a course on Moodle with great resources.)

Moodle

Most of us are familiar with the tool (or some other kind of Learning Management System like Canvas, Blackboard and etc.). It is important to have a centralized landing platform for students to access the courses and these LMS systems serve this purpose well. For us at CEU, this has been Moodle (or as some of you would know it, e-learning and later ceulearning, both built on the Moodle platform). This will continue to be the foundations of online classes. The functionality of Moodle is quite endless and I know for a fact that the CEU Moodle team is hard at work integrating the below mentioned tools (and more) for smooth interoperability, along with also upgrading the platform visuals for a more modern look.

Asynchronous Teaching (The Lecture)

The idea is to separate the teaching of the material into lectures that are unidirectional knowledge transfers which can easily be done asynchronously and other sections (such as social learning, group work, in class discussions, Q&A and etc. – more on this later). Even in regular teaching times, the, so called, flipped classroom model is a useful tool. There, the pre-recorded content is short and lays the foundation of the in-class discussion or activities. With a fully online course, a pre-recorded lecture will be longer, though not as long as an in class lecture in a small group where discussions interrupt the material the instructor plans to deliver.

A few tips on lectures. Again, (1) If the material can be divided into smaller parts, divide it. It is best to have 10-15 minute bits. If the material cannot be divided naturally, that is fine as well, but use division when you can. (2) If your class is in the 15-60 people range, you probably still have some interaction during the lecture. Your recorded lectures will (and should) be shorter when covering the same material. (Estimate roughly half.) In fact, on a video you may want to go a bit faster than in a regular in-person lecture not to bore people. (Remember, people can pause the video. (3) Try to speak in an interesting way. Try not to be monotonic. And, if it is possible, provide closed captioning. There are a few tools out there to do this. (Not sure if Panopto will do it. YouTube does it automatically. And you can find some additional tools if you look.)

Panopto

Here are some materials that will help you visualize what a good online lecture could look like without professional production facilities. Many (paid) online courses or monetized YouTube tutorials rely heavily on a high production value, they are recorded in a studio, produced professionally, but this is not something most of us will not have the ability to do. It is also not necessary to offer quality. Remember, quality comes from the content.

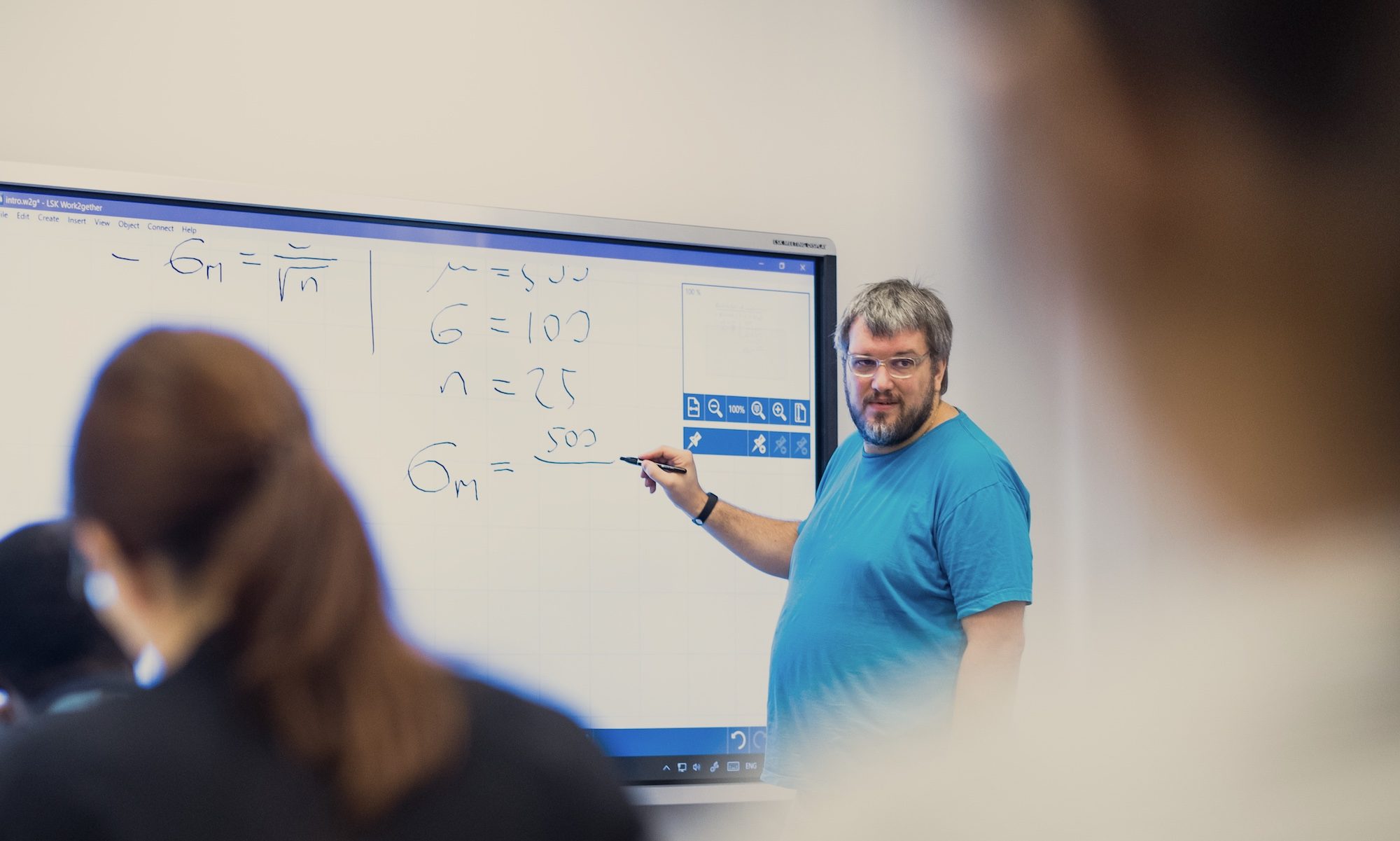

CEU has a Panopto license which will be at the core of strategy to help people move their lectures online and it is truly a great tool for this. Here’s an example of a Panopto lecture (recorded probably without much special equipment like a laptop camera and laptop mic – you can of course up your game with a better camera, microphone and lights). This example uses PowerPoint Slides but a board is also available which could be recorded on a Smart Board in the building or an Stylus supporting tablet (sorry, I don’t have such a video):

https://demo.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=1e9a9689-9882-4625-9471-444b4c9bb54e

Panopto can even be used more creatively. Not so much applicable for the social sciences, but look at this biology class utilizing a microscope with a built in camera.

https://demo.hosted.panopto.com/Panopto/Pages/Viewer.aspx?id=c1cfa29b-2bc7-4739-8e08-46143d9d1e55

Panopto can augment videos with quizzes pointing to the most important materials guiding the students what should be at the center of a potential live discussion, for example on Zoom. Here’s how:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TAPrM8jHTtM

Panopto can also be used to record in-class lectures. Less than ideal for the asynchronous format, but in a pinch, it could work. Separation between (the recorded) lecture elements of the courses and the interactive component of such recorded classes is key (like one would do in a large auditorium). Classes where the flow is constantly interrupted or that are seemingly unstructured discussions are not ideal for recording and yield a poor experience for the students watching the recording. So some adjustment may be needed when one decides to record an in class lecture. But it is the same adjustment one would do to talk to a large crowd in a large auditorium. Maybe we are not used to this at CEU where class sizes are kept relatively small, but we certainly can easily make this adjustment.

If Not Panopto

If someone wants to move out of Panopto and use some basic video editing tools, it is entirely possible to set up videos of different styles. This one is a particular favorite of mine (a video ironically reviewing Massive Open Online Courses).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0fp60iHV7Rk

I teach quite a bit of statistics. For this type of material, I am a fan of the Khan Academy format. Here’s a course with material that could have easily been in one of my classes (if it wasn’t for the fact that my handwriting is so horrible).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DaBq0naj0YY

And you can always just record yourself giving a talk and place it into the corner of a PowerPoint. To best make this work, use a 16:9 aspect ratio for the slides (because this is the size of videos) and leave an area for your image to be inserted. Pro tip: if you make a background with a small dark box the size of the recording you use, you will always know what area you need to leave blank on the slide.The tip also works for handwriting on smart-boards and tablets. Just tape off a corner and then you will never write over that area..

These types of videos require more video editing. For this I would recommend some free tools: iMovie (on a Mac) and I have been recommended Movavi for Windows (but will have to report back on how it worked once I tried it – yes, I intend to test it soon). Sometimes you just need audio editing options. For this, I recommend the free, platform independent, and incredibly flexible Audacity.

At the end of this post, I will also include additional tips for improving the production value of pre-recorded materials, how to think about potential equipment use and even some DIY tips on how to make equipment on the cheap. But first I would like to get to additional components central to the learning experience.

Other Tools To Augment The Asynchronous Experience (H5P and Perusall)

Panopto offers you embedded quizzes, but these other types of videos can also be augmented by an even larger array of activities. Look into H5P for this, which CEU’s Moodle fully supports. Here’s a good introductory video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2HtxLeXGU48

I can easily say that the coolest tool I came across in my search was Perusall. With it, you can turn the reading experience into a social experience. When access to the instructor is limited by distance, it is advisable to annotate assigned readings, ask questions, make comments to the students. It enhances the experience of the students feeling like the instructor is specifically talking to them commenting on the readings. (Also, if you ask some easy questions, it may help everyone feel included. Not just the most advanced students. So try that.) While this can be done easily in a PDF, Perusall takes this to a whole new level where students can also, socially, comment and discuss the reading materials. Here’s an introduction of the platform. (Sidenote: one of the developers of this platform is Gary King, a political scientist and methodologist at Harvard.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxEfWdfxj28

While clearly developed for undergrads, I have had luck using Perusall with grad students. Their business model is to sell textbooks to students, but they also allow the uploading of PDFs. If you assign journal articles or book chapters, this also works great (though stay away from poor quality scans and we will need to sort the copyright issues, but I understand the CEU library team is already on this). I did a webinar with Harvard Physics Professor Eric Mazur who is one of the brains behind the platform. He gave a few recommendations. (1) Don’t comment on what students say. You do not want to create an environment where students ask questions and the instructor offers the answers. (Or worse, an expectation that you will be present 24 hours a day to respond.) Let the students discuss. (I suppose it is OK to upvote or star when someone gives a thoughtful response. And in my workshop I offered responses but only after the lecture where we covered the material at hand.) (2) Turn on the Machine Learning algorithm for grading. The platform can actually grade students automatically (if the group is large enough, if I recall, 15 is the lower limit). I suspect this may not work so well in graduate school. I don’t suppose the platform can distinguish between high level of engagement and highly articulate nonsense and highly articulate thoughtful comments, but for the rest of the spectrum (inadequate engagement) it should be good. It is probably good up to the 80th percentile of the grading scale and the rest needs to be bumped manually for especially thoughtful comments (which makes the work easier for sure).

Synchronous Components

And there are components of the course where synchronous communication will need to take place. The biggest challenge here is time zones. Departments will have a hell of a time scheduling synchronous components for multiple time zones. But it will have to be done and some synchronous class components will have to be done twice.

Zoom (please, let’s stop using Teams)

I realize Zoom has been controversial. This is mainly because of the publicity the company received for Zoom bombing (people crashing meetings immediately broadcasting pron or racist content). The reality of this situation is that it could have happened on any other platform where open links were broadly distributed. Zoom was just the most used once the pandemic hit because it was the best, it ate the lowest amount of bandwidth, and it had the least amount of lag issues. Zoom is very flexible allowing for an array of interactions between instructor and students during a traditional lecture (though this format should be avoided) including yes, no, go faster, go slower, thumbs up, clap, raise hand. Features such as break out groups offer powerful tools in teaching. (Yes, we tested it in our pilots with excellent results. It is even useful for social activities where with 20 people everyone is quiet but in groups of 6 the conversation is vibrant.) If one knows how to use Zoom’s settings, the security issues go away. Other issues that point beyond Zoom bombing have been addressed in Zoom 5.0, so make sure you have an up to date version installed.

Zoom is useful for live Q&As, class discussions, synchronous group activities and all forms of interactions you may want to do live with the students. It can be used for lectures as well though if one is going to lecture, it is best to just pre-record it.

Here are the video resources I recommend for getting up to speed with Zoom.

Managing Participants: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozJS9bvdVp8

Break Out Rooms: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jbPpdyn16sY

Sharing Your Screen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YA6SGQlVmcA

How everyone can share their screens (useful for coding classes): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pt-tcvaQ9I4&feature=youtu.be

Using a tablet as a white board in Zoom: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SCr010CMRsg

And there are additional tips and tricks we should keep in mind. First set the tone for your workshop. You will have to walk a fine line between not being intrusive to people’s lives but insisting on them being present. Courses work best when everyone has good bandwidth, everyone is engaged and everyone has their camera on. Unlike in Teams, you can put a lot of faces on one monitor in Zoom. If there is some reason they need to turn their video off either temporarily or for a whole session, it is fine but try to avoid students falling into the habit of participating with their screens off (if bandwidth allows). How you set the tone about this early on will matter. Etiquette also calls for you looking at the camera when they are talking. (This is extremely hard when your screen shows, say slides or shared screen, and their faces are on another screen next to you.) Everyone should mute their mics when not speaking. (And Zoom allows the host to mute them as well if needed. Sometimes people forget their mic on and start to have a conversation with someone who walked into the room.) Obviously people should only use the chat for useful stuff. As instructors, it is extremely hard to monitor the chat while teaching. But it is still useful for the students for interaction. Don’t host alone. Hopefully you will have a teaching assistant. But if not, plan roles for the students. Ask them to help each other with technology issues. (This was especially important when teaching the software component of a class.)

Slack

Slack is an excellent software to build a learning community where people can interact in various contexts. It would give a platform for people to discuss the class. Instructors can chip in. (I would schedule set times for the instructors to answer questions. But you can also easily follow the fluid class discussion and put a like or heart next to good answers people give to each other, offering some insight if the discussion is heading the right or wrong direction.

Here’s an example video of how one person uses Slack for a class. But I could imagine a whole department setting up a common account with all the courses, with rooms for tracks, specific courses, specific instructors where questions can be posed to them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8K_N0YCBktU

Tech Tools for Teaching Coding

For more technical courses which require statistical analysis or coding (which may be relevant for Econ, Network Science, Cognitive Science, Public Policy or even some Political Science Classes) there are multiple tools available. Building your own server based infrastructure can certainly be very helpful. I have done this before with R-Studio Server when I needed to teach in a lab where I did not know what will be installed or even if users will have permissions to install, say R packages. The issue is certainly similar on whatever computers people use at home. Amazon AWS infrastructure can be very useful in these instances (if you don’t have your own server). I am in the middle of exploring more such options. On my radar are rstudio.cloud, codeshare.io and I have personally used Google Colaboratory.

Google Colaboratory (or Colab) was designed for the teaching of machine learning applications in Python. Here’s how it works. You upload (or create a new) Jupyter notebook in Google Drive which you can open with Colab. Inside you can use a very simple markup language for communicating information with students in an organized way, you can embed code which you can run on the spot on their free server. It is not very fast but it offers RAM, CPU and GPU. And there are other similar platforms out there as well (but I did not go down this rabbit hole… yet). See here:

https://www.r-craft.org/r-news/six-easy-ways-to-run-your-jupyter-notebook-in-the-cloud/

and here:

https://analyticsindiamag.com/5-alternatives-to-google-colab-for-data-scientists/

And now, Colab also works with R. It is a bit annoying how packages you may want to use (and are not installed by default) you have to compile from source (just like in R on any Linux machine). But beyond that it was pretty easy to use. Here’s a screenshot which may help you imagine how it looks and feels a little better. Once the notebook is created it can be shared both online and offline. And the students working in their notebook in Google Drive can easily share their work with the instructor/TA “just like how one can share a Google Docs document and even work in it simultaneously.)

One big downside of this platform is that it requires a Google account. But I have no problem asking someone to set one up just for the class, even if they are opposed to having a Google account (or do not wish to use their personal account for work/school purposes). It may cause some friction.

There is one big caveat to these technical components. We need to be very serious about moving to accessible platforms for everyone. This means a painful (for many) move away from Stata. Students will not have licenses. We cannot rely on computer labs. (Those things are a thing of the past.) I know Stata (for me Mplus) are sometimes the best tools for many jobs, but in our teaching, it is crucial to move to platforms that are open and accessible to everyone.

Production Value of Videos

Finally, I have also compiled a few videos with advice on how to improve the production value of video recordings.

How to build a video studio at home (with great discussions on shooting, background, placement, lighting – no need to take all the advice but it is a good list of what to think about): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TAw-xGSd83I

Cheap gadgets that can help (not necessarily these specific ones, but ones like these): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ruDJgtcZB-E

If you want an alternative set up for a white board (that is not just your tablet) this is a good one (especially the second set up presented which only uses a mobile phone camera). The video is intended for people who want to record drawings, but I could easily see it as a whit board alternative. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uzv8bxqvXy8

How to build a cheap studio light: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IFON04_L3zk

How to make a cheap green screen: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4wySe_NqfEU

If you want to know more about cinematic lighting, and how people use it for youtube (or teaching) videos, this is a good introduction: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G6W5wbPqzPw

I use a DIY studio key light built from a metal cookie tin box and a ring light from the cheap gadgets video as a fill (in a basement room with practically no natural light). Nothing else for now, but working on it.